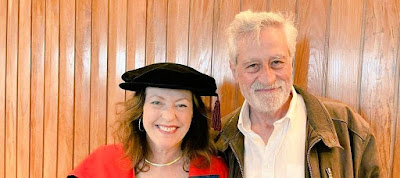

Weird event of the week was attending a King's College London graduation day at the magnificent Royal Festival Hall. Having left this university unnecessarily, under a humiliating cloud entirely of Management making, I was nervous and dragged my husband along to protect me from The Evil Eye. But I soon felt comfortable on meeting some of my favourite former colleagues, whom I miss sorely: Hugh Bowden, Emily Pillinger-Avlamis, and Will Wootton. |

| With Father of My Children, Who Offered to Bring an Electric Drill for Some Reason |

I was there to receive an award for being the best PhD supervisor in Arts and Humanities. There was a fruity irony in one Dean's office deciding to bestow this on me, thanks to the amazing testimonials provided by my lovely PhDs, when another Dean's office was spending hours devising ways effectively to demote me.

|

| With lovely former colleagues Emily Pillinger-Avlamis and Will Wootton |

Unfortunately nobody warned me that the tube in which the diploma to be awarded was actually empty, and my husband caught a photo of me staring inside it in some confusion.

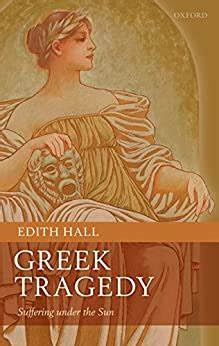

I was asked last summer to provide a statement about my supervisory theory and practice to go on the KCL website. Unsurprisingly, it has never been posted, presumably because I do not work for that institution any more. So just in case anybody out there is remotely interested, here is what I wrote: |

| With Professor Hugh Bowden, Superb Town Crier at the Event |

My supervisory practice

is founded in the philosophical approach inaugurated by Sara Ruddick’s Maternal

Thinking (1989), which emphasises that society needs to shape the care and

education of each citizen as a mother does for each of her children. This is

supplemented by Aristotle’s belief that every one of us has a potential (dynamis)

to be the best possible version of ourselves, but that to fulfil it one needs

sensitive and caring support from others.

I try to look after each

supervisee from the moment they contact me with a view to studying for a

research degree onwards, helping them frame the research question in their

applications and exploring their motivation, skillsets and potential to cope

with for the long, hard, lonely effort that writing a dissertation entails. I

try discreetly to discover how well they are supported financially and emotionally

in order to shape advice and support to their individual needs and make them

feel confident and welcome.

The reference works in

Classics are numerous and extremely complicated to use. Students, especially

from unconventional backgrounds, are often intimidated by them. When

supervision commences, I introduce supervisees physically to the library and

online research tools they will need, advise on key mailing lists, societies

and online communities to enrol in, and introduce them to all my other current

PhD students in order to encourage mutual advice networks.

Clarity in terms of

expectations and timetabling are crucial. Together we often create a paper diagram

with optimal dates (receipt of written assignments, supervisions, first draft

of thesis plan, doxography, upgrade, research trips, receipt of first full

draft, selection of examiners). This is then adapted as

necessary across the months and years.

The single biggest

challenge intellectually is turning a research topic into an over-arching

research question. This needs to be formulated as a ‘why’ or ‘how’ question,

rather than a ‘what’ question (the last of which tends to elicit empirical and

descriptive lists rather than analytical writing). I never cease emphasising the

principle that every page of the thesis must be geared towards answering that question

and that any excursuses need justifying.

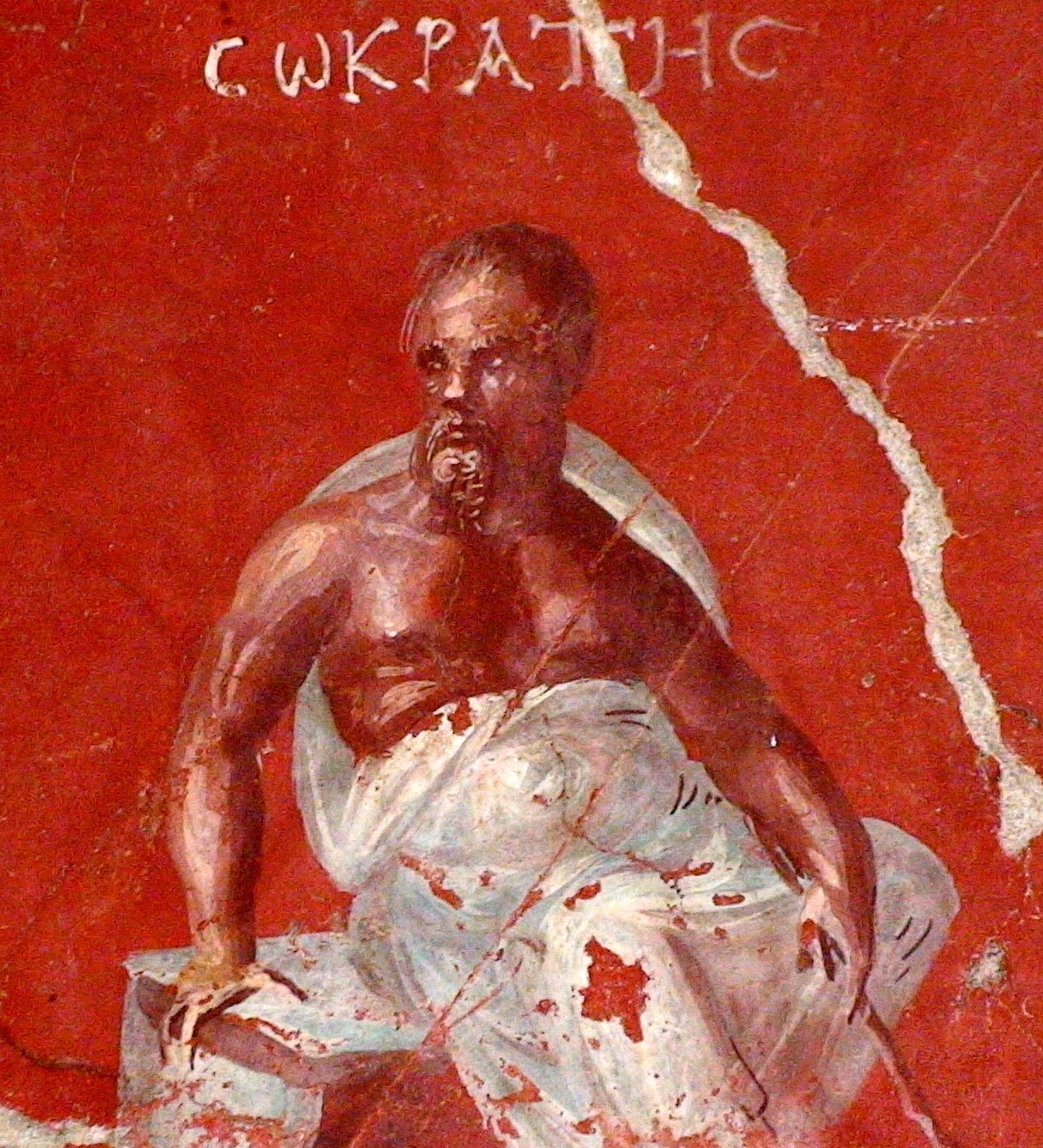

In feedback, kindness and

constructiveness are essential; intellectual confidence is a fragile thing. I

try to find something to praise in every piece of writing and guide supervisees’

thought processes by Socratic questioning rather than flat criticism which

tends to shut down discussion. I recommend the close study of the way in which scholars

write when supervisees say they admire it, in order for them to discover for

themselves what makes a convincing and elegant academic style. I hold ‘live’

rehearsals when they are to deliver papers at conferences or attend interviews and

work with them to improve the clarity, brevity, and enjoyability of their oral

performances.

But the most important

aspect of the supervisor’s relationship with graduate students is that it is quasi-parental,

even where the supervisee is considerably older than the supervisor. I make it

clear that I am happy to help at any time with personal difficulties, observe

the strictest confidence protocols, and always ask at the beginning of

supervisions how students are doing/feeling in general. I look out for

opportunities for them to deliver papers, publish, and network and train them

in how to do it for themselves. The point is to give them an intellectual

tractor of their own rather than a few years’ sustenance.

Finally, I do everything

I can to ensure that supervisees pursue successful careers or life goals when

they finish: I allocate an afternoon a week to reference writing. With the most

academically ambitious, I hold joint conferences and train them in co-editing

published volumes. I have been consultant on their theatrical productions and

have helped them publish their dissertations as monographs or series of articles.

I continue to meet them regularly either in person, often on theatre trips, or virtually for the rest of

our lives. A PhD student is for life, not just for a PhD.