Seven weeks after the British Library was afflicted by a ransomware cyber-attack, its chief executive, Sir Roly Keating, has belatedly issued a substantial statement. While it is indisputable that the attack has been perpetrated by a dastardly criminal group, in my opinion Keating’s statement strikes discordant notes and leaves us with more questions than answers.

First, although Keating

claims this kind of attack ‘was something we had prepared for and rehearsed,

and had taken steps to guard against’, the protective systems of which he was

in charge failed. It would be good to hear him concede this. It would also be

good to know exactly what plan the library had in place for such an event?

Second, the best way to

protect against Ransomware is to have a clean backup of data. If the library

had backed it all up, why can't it be reinstalled straightaway and we can all get back to normal? Or

did the hackers encrypt a backup too? That might suggest negligence on the part

of the library.

Third, the British

Library is publicly funded. Assuming no public money has been paid to hackers,

that still leaves the costs of remediation: are these coming out of the public

purse, and if so, what sums are involved?

Fourth, BL employees

have had their personal details including bank accounts hacked. Users like

myself have also had personal data hacked. Might a public apology be appropriate?

Fifth, why does it

remain impossible to order on-site materials to the Reading Rooms so many weeks

after the attack? I do not understand why a book or manuscript cannot be

ordered using a piece of paper and a pencil, and then be collected from the

stacks by one of the many members of staff currently sitting around in the

Reading Rooms looking miserable. Such a blindingly obvious resilience measure

should have been in place ever since the process by which books are ordered was

first computerised.

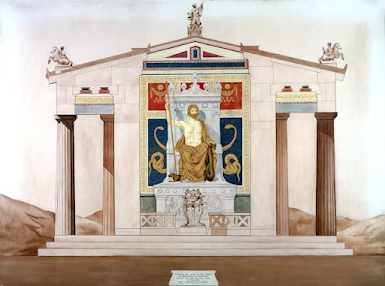

It was simpler getting books off shelves in Alexandria

Sixth, why has the information

about what is available been desperately misleading? Users

were sent an email stating that materials ordered before 28th October would be

delivered to Reading Rooms. I was victim to this misinformation myself when on

1st December I visited to read materials I had ordered in early October. The (non-tragic) result was a comically incomplete paper at my own conference on the Aeneid last

week; it consisted of a string of research questions rather than an argument.

The Reading Room staff were deeply apologetic, but not so Sir Roly, it

transpires.

Seventh, is Sir Roly aware that this particular piece of misinformation has cost Readers a lot of money? My futile

trip to London cost me less than £100, which (unlike my students) I can grudgingly afford.

But Rachel Mann (Uni Texas Rio Grande Valley) and Rebecca Long (University of

Louisville), two American Professors of Music beside whom I sat in the

otherwise deserted Rare Books Room, had spent thousands of dollars on

transatlantic flights to consult papers they assumed from the Library’s email

communication would be available. Other overseas individuals have got in touch

with me, after I spoke on BBC Radio 4’s ‘PM’ programme about the issue, with

similar stories of frustration and financial loss. Yet another Reason to be

Embarrassed to be British.

Eighth, students,

especially those writing dissertations on rare materials and postgraduate

researchers, are in serious trouble over deadlines. Not a word of

acknowledgement of their problems is said by the Chief Executive, let alone an

apology. I met a PhD candidate who is travelling to Paris to the Bibliothèque

Nationale to get hold of rare materials to meet their submission date. More

advanced academics who need to publish to secure tenure or promotion face

serious consequences for their careers.

And, ninth, Keating’s

statement is still desperately vague over when specific services will be

restored: ‘From early in the new year you will begin to see a phased return of

certain key services’ is not particularly helpful. Nor is ‘Other interim

services will include increased on-site access to our manuscripts and special

collections’. So no specific plans can be

laid for the New Year. The backlog will also mean that the library will be

mobbed by frustrated users; queues for seats in Reading Rooms, which already

get crowded in the lead-up to Final Examinations, will be inevitable for weeks. What plans are in place to ameliorate this?

The overarching tone of

the statement is one of high-minded rage (with which we can all sympathise) combined with

a curious sense of helplessness. But anger doesn’t submit dissertations in time

for deadlines, write books, pay for what turns out to be pointless travel, secure promotions or

enable planning for research trips in the new year. Readers are in pain. A

certain amount of humility and contrition, as well as far more detailed

information about what happened and is going to happen, would have gone a long

way to alleviate it.