To mark the gravity of current horrors unfolding, a longer blog than usual, on Lesya Ukrainka (1871-1913), the founding mother of Ukrainian literature, and her identification with Euripides’ self-sacrificial Tauric—Crimean—Iphigenia.

Larysa Kosach, known under the nationalist pseudonym of Lesya Ukrainka, identified profoundly with Iphigenia. This was partly because she knew that the play was set in her own country, and in a part of it near Sevastopol which she had come to know and love. She had celebrated the landscapes of ‘Tauris’ in her poetry collection Crimean Recollections, written between 1890 and 1892 and inspired by the beautiful environment of the Crimean coastline.

Iphigenia's experience resonated with her own personal sense of being an exile. She had suffered great loneliness when she struggled with the early death, from tuberculosis, of her lover in 1901.

As a Ukrainian writer, she was in a dangerous position since publishing in her mother tongue was banned by the Russian Empire. As an active opponent of the Tsarist regime, and a Marxist, she was alienated from the prevailing political order; she had been affected, at the age of 9, by the arrest and five-year Siberian exile of her aunt Olena Kosach in a wave of persecution of political activists in St. Petersburg.

The little girl was motivated to write her first poem, and many of her later works continued to address political themes: the cycle The Songs of the Slaves is a protest against the political subjugation of her fatherland, written around the turn of the century.

Ukrainka was herself arrested in 1907, when suffering bitter disappointment at the failure of the 1905 revolution. Moreover, as an invalid with acute tuberculosis of the bone, she was forced by her health into long periods of convalescence in warmer climates as well as sanatoria in the Caucasus and Crimea. Already well into her thirties, she had not only endured a great deal of pain, but also felt emotionally, linguistically, culturally and politically isolated.

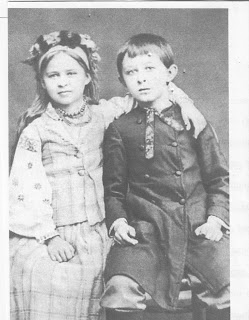

It is little wonder that she worked so intensely during this period on her ‘dramatic scene’, Iphigenia in Tauris, which she began in 1903. Her first language was Ukrainian, and much of her work is connected with Ukrainian folklore. But her avant-garde parents had educated her at home, along with her older brother Mykhaylo (she was the second of several children), in Greek and Latin as well as modern European languages.

Her favourite reading included Homer and Ovid (both of whom she translated), Sappho (about whom she wrote a poem), the Greek tragedians, Shakespeare, Maeterlinck, Mickiewicz, Ibsen, and Heine. Iphigenia in Tauris is the only ancient play she adapted—as a Ukrainian, who had spent time in ‘Taurida’, it would have been an obvious choice. But she takes Catherine the Great’s triumphant appropriation of the myth of the Greek presence in Tauris, and makes Iphigenia a resistant Ukrainian nationalist and radical, committed to struggling for a better world whatever the personal sacrifice.

The oppressive force in Ukrainka’s Tauris is wielded not by the barbarous enemies of Greece and Russia, but by Iphigenia’s captors, by implication the might of Tsarist Russia.

In the reception of Euripides’ tragedy, Ukrainka is singularly important, because she brought to the text an unprecedented fusion of classical scholarship and Ukrainian cultural identity. Her chorus are not Greek, as in Euripides, but local women of the town of Parthenizza; the play is set there, according to the detailed stage direction, ‘in front of the temple of Tauridian Artemis. A place on the seashore.’ (Vera Rich’s translation).

At a deep and subtle level of allegory, Artemis’ light can combat the darkness which the yoke of Russian imperialism has cast over all Ukraine. Iphigenia embarks on an 87-line soliloquy which expresses her innermost thoughts, memories, and suicidal anguish.

First, her homesickness—she left behind in Argos everything that bestows beauty on human life; family, renown, youth and love. There is an intense feeling that she is deprived of simple physical contact—the cold marble of her temple is no substitute for laying her head on her mother’s breast, to ‘listen to the beating of her heart’, nor for cuddling her little brother Orestes. Achilles, whom she loved sexually, must be in another woman’s arms by now.

The notorious wintry weather of Ukraine, noted in few adaptations of Iphigenia in Tauris, is turned by pathetic fallacy into an emblem of the frozen desolation in her soul:

How mournfully these cypresses are rustling!

The autumn wind...

And soon the winter wind

Will roar like a wild beast through all the oak grove,

The snowstorm sweep swirling across the sea,

And sea and sky dissolve again to chaos!

And I shall be beside a meagre fire,

Feeble and sick in body and in soul;

While there at home, in distant Argolis,

Eternal spring will bloom once more with beauty,

And Argive girls will go out to the woods

To pick anemones and violets,

And maybe...in their songs they will remember

Iphigenia the renowned, who early

Perished for her native land....

The autumn wind...

And soon the winter wind

Will roar like a wild beast through all the oak grove,

The snowstorm sweep swirling across the sea,

And sea and sky dissolve again to chaos!

And I shall be beside a meagre fire,

Feeble and sick in body and in soul;

While there at home, in distant Argolis,

Eternal spring will bloom once more with beauty,

And Argive girls will go out to the woods

To pick anemones and violets,

And maybe...in their songs they will remember

Iphigenia the renowned, who early

Perished for her native land....

Looking for metaphysical answers to the problem of her suffering, she tells herself not to contend against the supreme powers that rule the earth, nor the god who hurls the thunderbolt. But her inner self is in restless dialogue. Ukrainka opposes the idea that she should meekly accept her god-ordained fate by asserting that Prometheus had given her the courage to offer her life for her country:

You, O Prometheus, great and unforgotten,

Gave us our heritage!

The spark you snatched

From the jealous Olympians for us,

I feel the flames of it within my soul,--

And like a conflagration, unsubmissive,

That flame of old dried up my girlish tears

When I went boldly as a sacrifice

For the glory and honour of my Hellas.

Iphigenia is on the brink of suicide, pressing a sword from the altar to her heart, angrily asking Artemis why she saved her for such a wretched existence. But once again her courageous, enduring self becomes dominant. Suicide would be unworthy, she says, of a descendant of Prometheus: the true sacrifice demanded of her, she now understands, is that she must live in Tauris without people even knowing who she really is: ‘Let it be so’, she quietly concludes, but ‘Bitter is your heritage, O father Prometheus’.

While this ‘dramatic scene’ is complete as it stands, and concludes with Iphigenia walking resolutely, ‘with even steps’, back into her temple, we do not know whether Ukrainka intended to incorporate it into a longer piece or not.

It would be good to know if she had meant to include an Orestes, since she was deeply attached to older brother Mykhalo, with whom she shared the political and artistic project of translating great works of literature into Ukrainian—the bible, Gogol, Heine and Byron. In childhood they had been inseparable, and they collaborated on performing dramatic episodes from Greek mythology, ‘in which Mykhalo always assumed the role of the hero, while Lesya was the virtuous maiden or wife’. It is not at all improbable that they enacted the Euripidean play set in their own Ukrainian land, in which brother and sister are reunited.

As a very young girl, Ukrainka had also organised stagings of both the Iliad and the Odyssey with other little girls in Volhynia, and it would be fascinating to know whether it was the women or the men in those ancient epics in whom she was most interested, since in the cases of the bible and Greek tragedy, her readings were distinctively gendered. In the voices of ancient Greek heroines she found a medium where she could fuse her personal emotional history, her political polemic and a ‘universalising’ mythical referent that transcended the particularities of her own situation.

She was ‘especially moved’ by the heroine of the Sophoclean Antigone, and the style of the ancient Greek tragedies ‘strongly’ affected her dramatic writing. In her play On the Ruins she tried to inspire her countrymen to great deeds of self-sacrifice through the words of the prophetess Tirsa, who exhorts her fellow Jews to liberate themselves from Babylonian captivity. This strategy is similar to the uses to which she put the Trojan prophetess in her Cassandra.

Ukrainka was a communist and a Ukrainian nationalist as well as a feminist. Her Iphigenia in Tauris was designed to stand alone, as an independent performed drama. It has been staged in the Ukraine and in 1921 was used as the libretto by the Kiyiv composer Kyrylo Stetsenko. It's surely time for a revival.