For once I’m speechless. It’s Thursday lunchtime and in the last 330 hours I have talked publicly about 7 different ancient Greek topics and one Roman one. Conference season is always exhausting, but this year, with relaxation of Covid restrictions, has been exceptional.

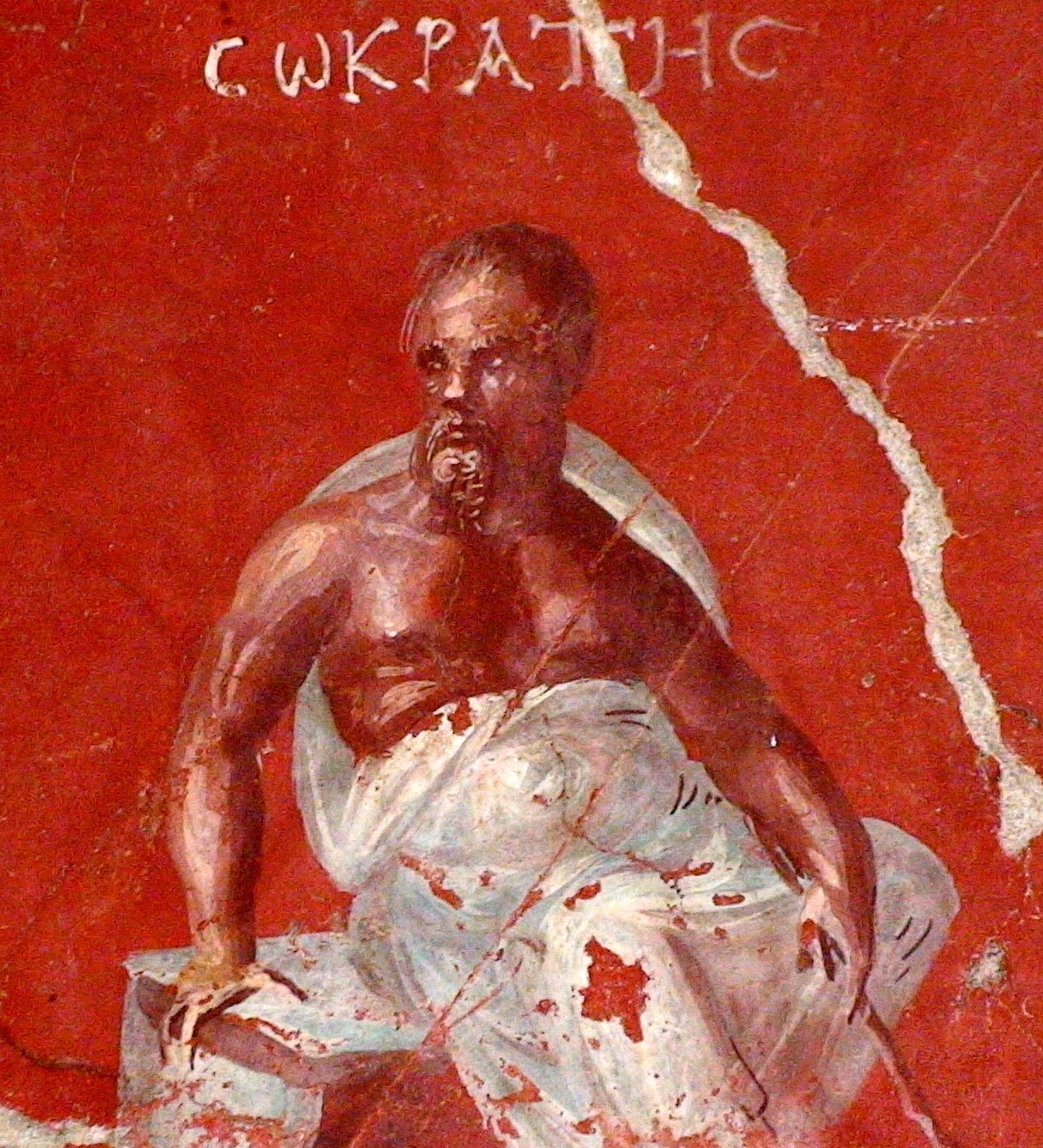

First up was a paper at a Durham conference on the image of the intellectual in antiquity. I pointed out that at the time of Aristophanes’ Clouds Socrates was only in his forties, famous for particularly thuggish performances as a hoplite, and therefore probably played by his actor as muscular, violent and domineering rather than a geriatric sage.

Next was an extraordinary version of Terence’s Latin

comedy Eunuchus by the libertine Restoration playwright Charles Sedley, revived

on ITV in the 1970s with Helen Mirren in the starring role. The seedy plot about

a man dressed as a eunuch raping a teenaged female is wholly unedifying but the

wisecracking is polished. This was an Oxford conference in association with the

Archive of Performances of Greek & Roman Drama I co-founded long ago.

From Oxford I hastened to the British Museum to add my

voice, as member of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, to a mass chorus of Greeks, Cypriots and others who want the

BM To Do The Obviously Right Thing. This will happen within my lifetime, I am

convinced.

Then I made an emotional return to my mentees at King’s

College London, my relationship with whom no Management berserkers can destroy.

I spoke to introduce their wonderful Plague at Thebes, an Antigone/Oedipus

fusion performed as the KCL Greek play. Marcus Bell and David Bullen: you

gentlemen rock.

Deftly locating a train during the week of a strike I

wholly support, despite Mike Lynch of the RMT rhetorically picking on Classics

as an example of an education that does not prepare one for running a nation's infrastructure, I got back to Durham in time to talk

about Tony Harrison’s brilliant poetic responses to fragmentary papyrus texts,

especially in his personal Ars Poetica, ‘Reading the Rolls’, in this volume.

Continuing the Harrison theme, I then went to Leeds to

introduce a screening of Harrison’s movie Prometheus organized by

stalwart Labour MP for Leeds East, Richard Burgon. It is a joy to find someone

with a Leeds accent who knows as much of Harrison off by heart as I do. We

visited the poet’s childhood home and the cemetery where his most famous poem, ‘v.’,

is set.

I feel exhausted as I write. The next words were in Durham Cathedral after I was deeply honoured to receive an Honorary Doctorate from the Chancellor, Sir Thomas Allen, a local lad who became an opera singer and inspired Lee Hall’s Billy Elliott. I used the occasion to pay tribute to the wonderful Professor Peter Rhodes, who served as Professor of Ancient History in the Department for decades before his recent sad death. He was a beacon of human decency at a time when it is hard to locate anywhere in public life.

Then, last night, I talked about the athletic, brutal,

dancing, Artemis-loving women of ancient Sparta at the recording of the incomparable

Nat Haynes’ latest episode of her radio show where she Stands Up for the Classics. My friend over 45 years Paul Cartledge coruscated as much as she did;

she also summarized the Odyssey in 28 minutes flat and with

sidesplitting humour. I’ll let you know when it is being broadcast.

I’m off to the Isle of Dogs to talk about satyr plays

after a rare performance by Thiasos Theatre of Euripides’ Cyclops on Saturday

afternoon. There are still a few tickets left. A good use of a summer Saturday

afternoon. But right now I’ve exhausted myself merely putting this on record

and will be catching up on Eastenders with a large pot of tea.