|

| Greek cartoon version of Knights |

In English texts until the Civil War,

the term dispassionately describes leaders of popular factions within ancient

republics. It was the beheading of

Charles I in January 1649 that irrevocably affected the meaning. In Charles’

purported spiritual autobiography, the Eikon

Basilike published ten days after his execution, he says everyone knows who

aroused the people against him: ‘Who were the chief Demagogues and Patrones of

Tumults’ who had tried ‘to flatter and embolden them, to direct and tune their

clamorous importunities?’

But Milton saw what this Royalist propaganda had done

to the term demagogue. His response, Eikonoklastes¸

remarked on ‘the affrightment of this Goblin word’ and said that these

Demagogues were actually ‘good Patriots’, ‘Men of some repute for parts and

pietie’ for whom there was ‘urgent cause’.

|

| Paul Cartledge |

Despite Milton’s protest, the word,

with sneering associations, became standard currency in English thenceforward.

This in turn affected the way historians read ancient Greek. So through a

toxic, uncritical dialogue with Thucydides and Aristophanes, Cleon became not

the archetypal leader of the people, but the archetypal ‘patron of tumult’, or

as Don Marquis perceptively put it, any ‘person with whom we disagree as to

which gang should mismanage the country’.

Men who have been accused of being ‘demagogues’ occur on all points of

the political spectrum: Charles James Fox and Tom Paine, Robespierre and

Boulanger, Gerry Adams and Ian Paisley, Adolf Hitler and Arthur Scargill.

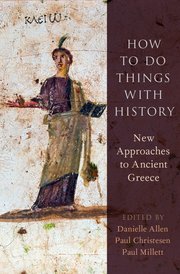

A new book How to Do Things with History has just been published in honour of my

friend of thirty years, Professor Paul Cartledge.* My own essay (of which I’m

happy to send a pdf to anyone emailing me at my two names separated by a dot

@kcl.ac.uk) argues that we have let our prejudiced sources on the Ur-demagogue

Cleon, a resolute supporter of the poorest category of Athenian citizens (thetes), taint our picture of everyone who stands up for the rights of the

under-classes ever since. Aristophanes and Thucydides do a hatchet job on

him, but both had personal reasons to dislike him and his loyal following

immensely.**

By

uncritically adopting their assessment, we forget (a) that Cleon’s

supporters thought that ‘leader of the demos’ was an honourable title and (b) that if any of their working-class

views had survived they would have told another story. A proportion of them may

have been newly emancipated slaves as well as those born into the thete class:

Aristotle tells us that freedmen, if asked to whom they would choose to entrust

their affairs, would automatically answer ‘Cleon’.***

There is also one precious source which shows

that a much more positive picture of Cleon circulated even in mainstream,

non-thetic citizen circles (Demosthenes 40.25). Plato probably didn’t follow Aristophanes and

Thucydides in attacking Cleon because Socrates respected Cleon and was loyal to

his memory, having fought on Cleon’s successful campaign to retrieve Athens’

imperial territories in the north. Socrates

stood in the battle lines at Amphipolis, as he says in the Apology (28e).

It is possible to be a People-Leader with

integrity. It is even possible to be a great orator with integrity. So let’s be

very careful with this “goblin word”.

|

| John Milton: Knew his Greek Better than Charles I |

* OUP, ed. by Danielle Allen, Paul Christesen,

and Paul Millett.

** I’m not the only or first person to argue this: see Neville Morley’s ‘Cleon the misunderstood?’ Omnibus 35 (1997) 4-6.

** I’m not the only or first person to argue this: see Neville Morley’s ‘Cleon the misunderstood?’ Omnibus 35 (1997) 4-6.

*** Rhetoric 3.1408b25.

No comments:

Post a Comment