|

| Greek mouse-shaped baby-feeder decorated with a hippocamp |

My office at King’s College London is

in an elderly wing often compared to a rabbit warren. But the mammal who

scuttled across it on Thursday afternoon was a mouse. This was during a two-day

conference I convened with my PhD student Connie Bloomfield-Gadêlha, which

combined papers on time, tense in different genres of ancient Greek literature

by scholars from 1st-year PhD status to distinguished Ivy League

professors.

|

| Roman bedside shelf for holding oil lamp |

I had been going to blog on what thirty

years of running conferences has taught me about ensuring their success: making

all sessions plenary, breaking up cliques, setting up running jokes, plentiful booze, talking

personally to every single delegate as well as every speaker, Stalinist timekeeping

with narcissistic mega-professors from one particular European country.

But ancient Greek mice, the stars of

several of Aesop’s fables discussed by our Bulgarian delegate Dimitar Dragnev, are

more interesting. I’ve always been puzzled by the infestation of the British

Museum with no fewer than fifteen classical mouse statuettes and several mouse-shaped baby-feeders. Both

Greeks and Romans liked decorating oil-lamps and shelves to hold them with mice, but why? As nocturnal animals? Symbolically to discourage mice from devouring oil and

wick? Because they are cute?

|

| Mouse on far right running away from ear of corn under Demeter's gaze |

My favourite mouse perches beside the

ear of corn on the coins of Metapontum; Demeter is arable goddess on the other side.

But the mouse’s strongest relationship was, strangely, with Apollo, least terrestrial

of gods. Around Troy his cult title, which features in the Iliad, was Smintheus,

Mousey (in some Greek dialects the word for mouse was not mus but

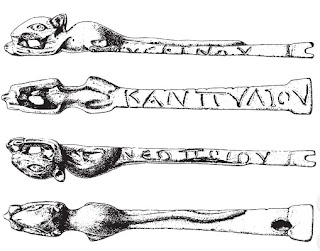

sminthos). Coins from the area showed him with a mouse, perhaps connecting the god of medicine with epidemics of plague. But some scraping tools shaped like a mouse’s whole

body, belonging to one Hygeinos Kanpylios, perhaps a doctor, have been said to be medical

instruments.

|

| Scraping Tools (Medical?) in the Shape of Mice |

The wonderful poet Alicia Stallings is

about to publish her translation of the bizarre ancient poem Battle of the

Frogs and Mice. If it’s as good as her versions of Lucretius and Hesiod, it

will be outstanding. The poem hilariously parodies the conventions of the Iliad

(Athena refuses to help the mice because they’re always gnawing the threads

she uses for weaving). There were other ancient burlesques featuring epic

battles between fauna: the hero of the war between the mice and weasels

preserved on Papyrus 6946 in Michigan is a mouse called Trixos, or ‘Sqeaky’. He is

slain and eaten by a dastardly weasel, leaving Mrs. Trixos widowed back

in Greece, ‘with both cheeks torn’.

Boris Johnson’s favourite saying is AUT HOMO AUT MUS? (Are you a man or a mouse?) When challenged to being

blasted by a water cannon, after ordering three to use on London streets in

2014, he eventually agreed, saying, ‘Man or mouse.You've challenged me, so I suppose I'm going to have to do it now' [Inevitably

he never did]. I haven’t found the saying in any ancient author, though am happy

to be corrected; what seems more appropriate to Johnson these days is the

Scottish mouse proverb immortalised by Robert Burns, The best laid schemes of mice an' men/Gang aft a-gley.

No comments:

Post a Comment