As if the world didn’t have enough

problems already, Donald Trump has pulled the USA out of the Paris Climate Agreement

which, for all its limitations, represented a multilateral human

acknowledgement that greenhouse gas emissions were wrecking our planet. Time

for a look at the history of awareness of the damage humans can do to the rest

of the natural world, an awareness already developed in the Father of

Zoology, Aristotle.

When he is describing shell-fish, we discover

that in the lagoon on Lesbos the red

scallop has actually been rendered extinct. It has been destroyed partly by droughts but also ‘partly by the dredging-machine used in their

capture’. This is probably the earliest reference to overfishing in world literature. Aristotle also cites the destruction

which can be cause by human interference, motivated by financial greed, with

naturally occurring animal populations. A Carpathian tried to make money out of

hare breeding, and introduced the first pair onto his island. Carpathos was

soon over-run with hares, which devastated its crops, vegetable beds and plant

ecology.

Aristotle is aware of the destructive

potential of farming, as a form of interference in natural processes. He even

suggests that kitchen vegetables flourish better if left to the elements than

if they are irrigated artificially. He certainly condemns some human practices

in the farming of animals as contrary to nature and pernicious.

Some animal breeders tried

to make the young males of certain species breed with their own mothers. This mother-son

inbreeding was attempted either because the owners could not afford to hire a

stud or because the animals they possessed were regarded as particularly fine specimens with specific attributes they wanted to perpetuate. This practice is

not unknown amongst breeders of pedigree dogs today, although it is rightly

regarded as genetically risky and abusive; line breeding, where animals mate

with distant cousins, is infinitely preferable. Aristotle is certain that

animals do not naturally want to mate with their mothers, and has

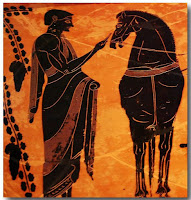

collected examples of animal resistance to enforced ‘Oedipalism’: ‘The male

camel declines intercourse with its mother; if his keeper tries compulsion, he

evinces disinclination.' On one occasion, when intercourse was being declined

by the young male, the keeper covered the mother and put the young male to her. But after the intercourse the young

male camel bit his keeper to death. In another example, he reports that a young

stallion forced to impregnate his own mother committed suicide by hurling himself of a cliff.

Some animal breeders tried

to make the young males of certain species breed with their own mothers. This mother-son

inbreeding was attempted either because the owners could not afford to hire a

stud or because the animals they possessed were regarded as particularly fine specimens with specific attributes they wanted to perpetuate. This practice is

not unknown amongst breeders of pedigree dogs today, although it is rightly

regarded as genetically risky and abusive; line breeding, where animals mate

with distant cousins, is infinitely preferable. Aristotle is certain that

animals do not naturally want to mate with their mothers, and has

collected examples of animal resistance to enforced ‘Oedipalism’: ‘The male

camel declines intercourse with its mother; if his keeper tries compulsion, he

evinces disinclination.' On one occasion, when intercourse was being declined

by the young male, the keeper covered the mother and put the young male to her. But after the intercourse the young

male camel bit his keeper to death. In another example, he reports that a young

stallion forced to impregnate his own mother committed suicide by hurling himself of a cliff.

Methods of raising and feeding horses worry

Aristotle. Horses should be allowed to roam freely at pasture, since then they

remain free of disease apart from an affliction of the hoof which is in any

case self-rectifying. But stables are breeding-grounds for malnutrition and all

forms of infection: ‘stall-reared horses are subject to very numerous forms of

disease: one which attacks the hind-legs’ (Equine Degenerative Myeloencephalopathy?)

Aristotle can have known nothing about

species resonance. Yet he tells us of an instance in 395 BCE. All the ravens

disappeared from southern Greece when a battle much further north resulted in a

particularly high death toll. Ravens are opportunistic carrion birds. Aristotle

calmly infers from this, that even across vast distances, ‘it would appear that

these birds have some means of intercommunicating with one another’. It’s a

pity Trump doesn’t have a similar means of inter-human communication.

No comments:

Post a Comment