I want to know what The Markets really are. I want to know because the news has been telling us how important The Markets are all week. Apparently, we need above all to entrust our livelihoods and governments to The Markets.

This raises an important question. Should humans really decide the shape and qualities of the world of the future with their brains or by responding mechanically to what The Markets tell them is required tomorrow?

In this momentous week we have seen the democratically elected leader of Greece replaced by an unelected individual of whom the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and The Markets approved. We know what the IMF and the ECB look like. But we do not have the slightest idea who or what The Markets actually are.

In this momentous week we have seen the democratically elected leader of Greece replaced by an unelected individual of whom the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and The Markets approved. We know what the IMF and the ECB look like. But we do not have the slightest idea who or what The Markets actually are. We do know, however, that The Markets liked it when Lucas Papademos was sworn in as Prime Minister in Greece. The Markets liked it when it became clear that Silvio Berlusconi would have to resign and that he would probably be replaced by Mario Monti.

The Markets are now in power, and allowed to tell The Greeks and The Italians who should govern them. Now I don’t have a problem with Papademos. He is clearly a sensible man as well as a banker. It is even more obvious that almost anybody would deserve greater respect as a leader than ‘Burlesquoni’. But I do not think that we have yet understood that there has been a terrifying takeover of the democratic system by a race of aliens about whom we know practically nothing.

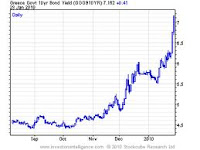

Do Markets look, for example, a bit like Meerkats? Or are they actually Meerkats? Perhaps their name reflects a simple phonetic shift whereby ‘a’ and ‘e’ become inverted. Perhaps they are Meerkats who live in houses inside real markets with marble fish slabs and fruit baskets. Or perhaps they are new breed of Meerkats who live in stock exchanges and eat crazy graphs with squiggles on showing ten-year bond yields.

Either way, we need to know. The Meerkat/Markets clearly want to run the world, and have just picked on the two countries which gave us Classics because they have a nasty sense of humour.

Or is it that they have been listening to the Senior Management Team at Royal Holloway?

The Markets, like Paul Layzell and his team, think that the future of universities should be dictated by supply and demand on a short-term basis.

In Classics at Royal Holloway, we are now told that although there will be fewer redundancies and none until 2014, they might still happen if ‘The Market’ for undergraduate degrees in Classics shifts downward. We scholars can’t ever try to design long-term research or teaching policies, because The Markets might suddenly remove vital colleagues or fail to replace them altogether.

Hiring and firing academics depending solely on the current ‘Markets’ is a not a completely new idea. But it is one that has always been resisted in cultured communities. This is because it means that crucial decisions about the sort of intellectual environment people want to live in are taken not by humans but by the new race of power-crazed Markets who are trying to take over the world.